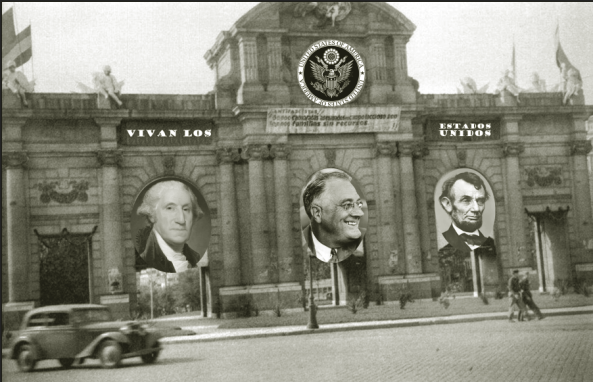

This photo of the Puerta de Alcalá in the now distant days of July 1937 continues to be the subject of controversy. It was taken during the celebration of US Independence Day in Madrid on July 4. The reason for this tribute was Spain’s gratitude for the help provided during the days of the coup that nearly caused a long and disastrous war in which victory would not have been assured. There is no doubt that Roosevelt’s courageous action in mid-July 1936, when he honored the arms purchases that the Republic had already made, would be key in the course of events.

The presence in Madrid of the 50 Martin Bomber B-10Bs purchased to serve while the Getafe factory where they would be produced under American license was being completed was key. The B-10s managed to help clear the Alto del León and neutralized Mola’s columns in the area, facilitating the advance to the Duero and the collapse of the rebels in the area they had occupied.

The Martin Bomber B-10B with factory registration and insignia arrived for evaluation and training in November 1935, flying between Getafe and Talavera. It was the first bomber with an all-aluminum fuselage and enclosed turrets; it had a flight range of 1,900 km. In March 1936, the government accelerated the closure of the aircraft purchase operation (four complete squadrons) in view of the delay in setting up the licensed factory in Spain.

On the other hand, the B-10B squadrons, taking turns one after another on the roads linking Seville with Extremadura, prevented the attempted advance towards Badajoz and Mérida, which might have taken the rebels to Talavera before forces could be gathered to contain them. After the arrival in Badajoz of reinforcements from Talavera under the command of Colonel Salafranca, a prestigious Africanist military officer, his leadership, together with that of Colonel Puigdengolas, succeeded in reorganizing the forces in the area. With Mola’s retreat to the northern plateau and the Talavera-Mérida-Badajoz line secured, Cáceres was liberated and fears that the southern rebel zone would connect with the north faded. The Air Force was key to this whole process.

B10-B bombers of the Spanish Republican Air Force flying over the Sierra Nevada in January 1937. They belong to the first squadron built in Spain under American license.

These undeniable triumphs sustained the Giral government in August 1936, which contributed to the stability of the republican state and led tens of thousands to join the army of volunteers that was being organized thanks also to the trade union and political organizations of the Popular Front. However, the main part of Roosevelt’s aid was in the economic sphere. Recalling, as he did in his famous speech to Congress, Spain’s aid during the American War of Independence, Roosevelt assured the Spanish state’s right to use its own national resources on the international market and to open accounts or use those it had in the United States. Similarly, as Spain was not officially at war with any other country, he argued that the law prohibiting exports to countries at war, which had been passed that year, did not apply. This was key.

Furthermore, as it was not a member of the League of Nations, the United States did not consider itself affected by the decisions taken under British pressure and opted for a bilateral relationship with Madrid. All this greatly strengthened the international position of the Giral government and gave indirect support to the position of the Blum government in Paris. The US ban on US companies selling oil to the rebels and the arrival of several ships with ammunition and weapons in Gijón, Bilbao, and Cartagena in September ensured the defense of the north and provided the new Mixed Brigades of the regular popular army of the Republic with sufficient supplies. Without this material and reorganization, it would not have been possible to isolate the Andalusian triangle occupied by the rebels (Seville, Granada, Cádiz) or advance to the Duero line. However, it has always been said that the decisive factor in the rapid conclusion of the war was France and not the United States.

As is well known, in September 1936, France ordered its troops to enter the Protectorate. The French Foreign Legion left Sidi Bel Bes and occupied the entire eastern part of Spanish Morocco. Marshal Pétain, commander-in-chief of the French forces, acted decisively and forcefully, neutralizing the rebel forces after a short struggle, as their main core was on the peninsula. France’s decision was in line with the Spanish-French mutual aid agreements signed years earlier. If they did not act at the beginning of the crisis, it was due to Paris’s fear of internal tensions in France, the spread of the conflict, and British pressure. But when the United States did not object to Madrid acting in defense of its rights and did not recognize the British veto, Paris made its move.

The instability in North Africa, the covert Italian and German intervention, and the need to strengthen the government of the Republicans led by Giral convinced Paris that intervening in Morocco was the best course of action. With Pétain in command of the armed forces in Morocco, there would be a guarantee that everything would be under control in that area, it would allow Madrid to be helped without further involvement on the peninsula, and it would also send a message to Rome and Berlin. Without the diplomatic connection between Washington, Paris, and Madrid, this move would not have been possible. Another consequence of this coordinated action was that the role played by the Soviet Union remained secondary and discreet, facilitating some recruitment of volunteers who would arrive in September, diplomatic support in the League of Nations, and some purchases of aviation and naval fuel and light weapons.

Indeed. It was enough for Roosevelt to recognize the Spanish state’s full right to defend its rights on the international stage and not to veto the purchase of weapons for the dynamics of events to favor Madrid’s efforts to defeat the uprising and ensure the republican institutionality in Spain. However, it was the internal social and political factor that managed to defeat the coup first and in the short war that followed. The alliance between Republicans and workers’ organizations had made the Popular Front possible, something that did not happen in Germany or Austria, and this would be key to the popular response to the coup and to the enormous social mobilization that followed. The military victories under the Giral government reinforced the political leadership of the Republicans.

Another factor, not always explicit, was that the USSR favored the mobilization of the communists and support for the government of the country, as part of its strategy to contain Nazism and seek an alliance with Paris and Washington. The withdrawal of rebel troops from Galicia and Zamora to Portugal in November 1936, the blockade of Navarre and the isolated triangle of Seville, Cadiz, and Granada marked the beginning of 1937 as the end of the war. We know how the story ends: Mola’s suicide in a cheap hotel in Biarritz, Franco’s exile in London via Lisbon, the flood of Carlist refugees across the snowy passes of the Pyrenees, and the impact on Portugal of the defeated troops and a large number of civilians.

In 1937, Spain was devastated by war, but it had managed to hold on. Internal political contradictions, mainly due to the social revolution in some areas such as Catalonia, were strong, but they were resolved constitutionally. Events in Europe, with the rise of Nazi expansionist policy, continued to unfold. The defeat of fascism in Spain boosted the morale of anti-fascists in France and throughout Europe, but it also revealed the danger of a new widespread war that many feared. Appeasement, promoted by England, gained ground, and when Germany raised the Czech question over the Sudetenland, London and Paris gave in, while a Spain that was still rebuilding and deeply wounded could do nothing but show solidarity with Prague.

After the Munich Conference, the United States once again realized that it was impossible to deal with the fascist powers, as England advocated, and defended what was called “containment from a distance,” which required a policy of neutrality, among other things, in order to strengthen itself internally.

The subsequent breakdown of all agreements between the European powers on the security of what remained of Czechoslovakia in March 1939 led to its invasion and partition between Germany, Poland, and Hungary. After this, even England had to acknowledge that the Nazi regime had its own agenda and would not allow itself to be manipulated, making the possibility of a new war a real one. The USSR realized that the possibility of an alliance with the French and British to contain Hitler was unfeasible and began to develop its own policy of containment to delay German aggression as long as possible. The United States did not want to interfere in European politics as just another player, as the result could be getting involved in a war that it did not want to encourage.

The United States’ actions towards Spain in 1936 had been limited but successful: it was enough to respect international law for the Spanish Republic to resolve its own internal crisis in just ten months. Had another path been taken, things could have been very different, including the possibility of direct military intervention by fascist Italy and Nazi Germany in Spain, which would have put the USSR in the position of having to decide whether to intervene in turn and to what extent. On the contrary, the fact that Spain was able to obtain the resources for its defense quickly was what prevented an escalation. What the Spanish crisis taught Washington was that intervening is not the same as meddling and that sometimes it is necessary to intervene just enough to avoid being dragged into an undesirable situation. It became clear to Washington how adventurous and risky British foreign policy in Spain was, because by attempting to establish an international blockade of the Spanish Republic, it was actually creating the conditions for direct German and Italian intervention in Spanish affairs.

After finding itself on the brink of the abyss and saving itself, Spain chose to rebuild and maintain strict neutrality, so Madrid had no problem following in Washington’s footsteps. With the Nazis in power in Germany and the progressive fall of all European democracies into authoritarian regimes, a huge flow of refugees was trying to escape; the difficulties in entering the United States led many to Spain. Indeed, after Kristallnacht in Germany, Spain received thousands of Jewish refugees from Germany and other countries that were falling into the hands of fascism. A neutral but supportive Spain, in the process of reconstruction, sought to avoid being dragged into a new war and was becoming a new Switzerland.

It is well known that international politics continued to follow their course and that after 1945 a Cold War arose between the Western bloc and the USSR, but the specific details of international politics between the partition of Czechoslovakia, the start of the world war, and the aggression against the USSR that gave rise to the great alliance that ultimately led to the Allied victory are often viewed very superficially. And in that period, Spain’s role is treated superficially. It is often not understood that Spain did not participate in the declaration of war that France and England made against Germany when Poland was attacked. This is often attributed to Soviet influence, as the Communist Party of Spain had a very strong influence on Spanish politics at that time, but this is an absurd simplification. The situation in Spain in 1939 is underestimated. The country was emerging from a short but brutal war that had torn it apart between July 1936 and February 1937. The internal divisions were very strong, and reconstruction was not easy in an international environment where there was a climate of confrontation and war. The last thing the Spanish people wanted was another conflict. This explained the enormous success in the 1938 elections of the left-wing and center-left republican parties when the PSOE abandoned the Popular Front and demanded entry into the government, a move by Largo Caballero that was very poorly received by his own social base, as the victory had been experienced by all as something collective and not just by the Republicans, while the social and economic transformations that had taken place during the war had been legalized without problems within the constitutional framework, as was the case with agricultural collectivization and the new factory and service cooperatives.

In President Azaña’s resignation speech, his words saying that it was time for Peace, Mercy, and Forgiveness fell like seeds on the stirred soil of Spain. With Giral as President of the Republic and Gordón Ordás, an energetic yet conciliatory Republican imbued with a sense of statehood, the Spain of 1939 was embarking on a different path, one of moral and physical reconstruction of the entire country.

The signing of the German-Soviet Pact brought the Spanish communists to the brink of internal rupture, but the orthodoxy of the party, and certainly its parliamentary group in the Cortes, came to support the government of Gordón Ordás when it kept Spain neutral in the first phase of the war, just as the United States did. The defeat of the French armies in early 1940 caused a crisis in the French Republic that led to the blockade of the government after they were forced to flee Paris, the debacle of the retreat to the south, and the formation of a Defense Junta that assumed all powers and placed them in the hands of Marshal Pétain, putting an end to the weak Third French Republic and giving rise to what became known as the French State, a reactionary regime that collaborated with Germany. The United States and Spain recognized the new French government, although Spain was filled with French refugees, civilians, and retreating troops who did not accept defeat and the armistice with the Germans; the Spanish Protectorate in Morocco remained under French control, and its military command was a staunch supporter of Pétain. The old Marshal, well aware that his military intervention in 1936 was what saved the Spanish Republic, did not hesitate to make the most of this fact and maneuvered diplomatically to try to consolidate Spain’s neutral role during that period. This fact, coupled with the undeniable reality that only England was continuing the war against Germany, led several prestigious military figures, such as General De Gaulle, to go to London, where they assumed the role of leaders of the resistance of a free France that did not accept defeat. Churchill openly supported De Gaulle for these reasons. One of Churchill’s fears was that France’s naval military potential would end up in German hands and that Hitler would consolidate his political control over continental Europe. Spain was politically hostile to England because of the role played by that power during the war of 1936-37, and Pétain’s France had surrendered. England needed allies in order to continue the war and win, thereby ensuring the survival and dominance of its ruling class, which would be threatened if the Nazis won, either through direct military occupation or an armistice that would lead to Nazi political victory.

The British path was to continue the fight against Germany alone, support the French who were in favor of resistance, and involve neutral countries such as the United States, Spain, and the Soviet Union in the fight as soon as possible. Their attempts to involve Spain in the fight did not work, although Spain did become non-belligerent and provided facilities to the Royal Navy in Spanish ports on the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts in support of the war effort. It was clear to England and the United States that Spain’s position was key at that time because of its dominant position at the exit of the Mediterranean and its Atlantic projection, but above all because its consolidated political sovereignty allowed it to freely orient its policy in the midst of the storm of war; These countries needed Spain’s alliance and needed to attract it to cooperate with the latent Anglo-American bloc and ward off any temptation to strengthen ties with the USSR. In Spain, the socialist and communist left accused Churchill of opportunism and crypto-fascism, in the sense that his resistance to Hitler was motivated solely by class interests and not by democratic convictions. The republican parties, for their part, saw the need to reestablish ties with London and deepen them with the United States, and they advocated a formally correct relationship with the USSR but at the greatest possible distance. The result of all this crossing of interests was that no one could afford to make hasty decisions about Spain’s entry into the war and the opening of a new front there, nor could the Spanish government deepen its relationship with the USSR. The United States supported Spanish neutrality, a benevolent neutrality towards the British resistance, sent numerous material and military aid, and encouraged Spanish governments to strengthen their relationship with England.

The German attack on the USSR in June 1941 changed things dramatically, and in Spain the communists demanded to join the fight and declare war on Germany. Gordón Ordás, in coordination with Roosevelt, kept Spain neutral even at that time, although he authorized a Spanish division of communist volunteers to march to the USSR to fight alongside them as another unit of the Red Army. The Spanish volunteers arrived in the USSR on British and Spanish ships, via England, the North Sea, and Murmansk, arriving in time to participate in the defense of Leningrad, where they fought with honor. It has always been said that this military mission, carried out despite Spanish neutrality, caused many of the most motivated Spanish communists to go off to fight far away, which served to reduce the internal tensions of the political situation facing the coalition government of republicans and socialists, the so-called Government of Peace. The German offensive in the USSR began very strongly and successfully, managing to destroy most of the Soviet forces concentrated in the western part of the country, but it ran out of steam in late autumn when the cost in irreplaceable casualties, insurmountable logistical difficulties, and above all the firm will of Soviet resistance and its ability to mobilize new armies – The German offensive on Moscow failed miserably and the prospect of a German victory in the war was shattered; the tide had turned.

In November 1941, as Nazi troops crashed against Moscow’s defenses, Japan launched a surprise attack on the heart of the U.S. Navy in the Pacific. The United States entered the war, and Germany in turn declared war on the United States. In January 1942, the Spanish Republic, coordinating its action with the United States and England, declared war on the Axis, becoming part of what would later be the victorious Alliance in World War II.

The United States gave preference to the European front and organized a landing in North Africa and the dispatch of troops and aircraft to Spain. The German response was to invade the unoccupied zone of France and defend the Pyrenees line, but they did not have the strength to enter the peninsula and fight the Spanish and Americans. While Allied troops landed in Morocco and Algeria, which meant entering the Spanish Protectorate in northern Morocco, Pétain’s government was divided. Supporters of accompanying Germany to the end were in the majority in the cabinet, but the Marshal, who had retired to the south of the country at the beginning of the crisis, entered Spain after reaching an agreement with the Spanish government. In coordinated action with Washington, General Giroux proclaimed the formation of a French government of national salvation in Algeria and offered cabinet posts to both those who had remained with Pétain and De Gaulle. The response of the openly fascist sectors was to proclaim a phantasmagorical French Social Republic, which was established in the Alps and completely devoted to Nazi Germany.

Between 1942 and 1945, the combination of Russian advances, Allied landings in Italy and France, Italy’s change of sides, and the total mobilization of the industrial and human power of the United States led the Allies to total victory. Spain played a very important role in this struggle. It did so in the diplomatic arena by playing its neutral role very well in coordination with Washington, it helped England in the Battle of the Atlantic by facilitating access to bases and intelligence from the Spanish coast, it served as a refuge for hundreds of thousands of refugees from all over Europe, and it served as a bridge and base for all supplies arriving from the United States. Militarily, its strategic position proved its value once activated, as, literally, upon entering the war, it cornered Italy in the Mediterranean, exerting decisive influence over the Strait of Gibraltar, the Atlantic, and southern France. In terms of military intervention, it was notable on the Mediterranean front and especially in the liberation of France, symbolic on the Soviet front and decisive in the Atlantic.

Knowing history, being the result of it, proposing alternative courses of events may not make much sense. With or without Spain, the Allies would have won the war against Nazi Germany. A hypothetical victory for the rebels in 1936 would have handed the country over to the Axis in one way or another, but above all it would have meant the destruction of Spain’s future as a democratic and developed country. In the summer of 1936, the insurrection by part of the army was initially defeated in most of the country, but when it triumphed in some areas and the armed forces were broken, the Spanish Republic could only survive because the people took up the fight as their own, organized by trade unions and anti-fascist political organizations and loyal sectors of the armed forces. The military victory over the colonial forces that had landed in the south, preventing their rapid advance northward thanks to the Air Force, allowed for a reorganization of the defense. If, in August 1936, the loyalist forces had been forced to retreat and Madrid had been threatened, the Giral government would have fallen and a hypothetical emergency government with the forces of the Popular Front would not have been able to win either if it did not have the resources to arm the army. It was no longer a question of political support or parliamentary or social backing; it was a war, and in war, victory or defeat is determined by factors of force. The war material purchased from the United States before the war and the fact that the United States did not participate in the economic and political blockade of the Spanish Republic were the external factors that enabled the democratic forces in Spain to win the war.

Given this background, it is not at all surprising that Spain remained a loyal ally of the United States until the sudden change of situation in Washington in 1947 as a result of the never-clarified assassination of President Henry Wallace, vice president at the death of Roosevelt in 1945, before he could revalidate his presidency at the polls that year.

The Cold War with the USSR and the formation of the Iron Curtain led to a completely new period. Republican Spain in that period once again showed its willingness to remain actively neutral and did not participate in NATO, maintaining formal relations with the USSR but clearly allied with the United States alongside the recovered France and Italy, now governed by the former anti-fascist leaders and political forces who had been forced into exile in Spain. In the early years of the United Nations, Spain, as a medium-sized power and prestigious for the success of its second republic based on a fraternal social model and its proven and undefeated anti-fascism, exercised a certain leadership in international relations in the face of the new Anglo-American bloc, helping the Hispanic countries and France and Italy to coordinate in a world now divided by the Cold War.

Decades later, at the beginning of the 21st century, things have changed a lot. Today, when Spain is the only European country without US bases, there is the paradox that it is the country that feels closest to the United States, where public opinion is closest to that nation. It is also the country where an old photo of the Puerta de Alcalá with the historical leaders of an allied country in a difficult time is manipulated by the reactionary opposition to attack the Spanish Republic for its historical respect for the sincere alliance with Roosevelt’s United States, now almost lost in memory.

At a time when we are commemorating how the Spanish Republic triumphed thanks to a brave people who knew how to defend their freedoms and independence, remembering the role played by the United States in that struggle is an essential exercise in historical memory. The memory of the alliance for freedom in those times inspires our solidarity with the American people, who today face the danger of seeing their constitution, their republic, and their rights and freedoms threatened. Spain does not forget those who stood by its side, and the Republic will always be fraternal with those who, no matter where they are, fight for the freedoms of the people.

Descubre más desde Sociología crítica

Suscríbete y recibe las últimas entradas en tu correo electrónico.

Posted on 2025/11/17

0